What Is Learned Helplessness

A close cousin of hopelessness can often manifest as helplessness, which can then manifest as learned helplessness. The experiment above showing the results of teaching dogs that they couldn’t escape a cage is a behavioral example of learned helplessness.

Hopelessness and depression can lead to learned helplessness. Learned helplessness can go hand in hand with hopelessness. Hopelessness can be characterized by feeling bleak about situations in one’s life. Helplessness comes into play when a person feels they can do nothing to change the situation, and that no outside source will change it.

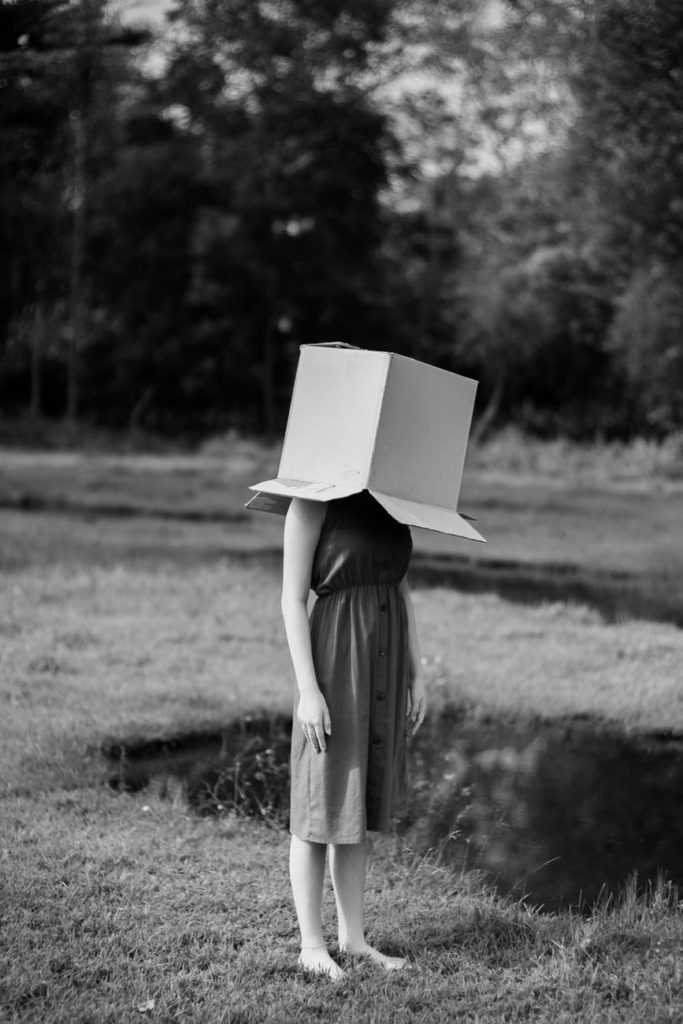

Most of us get tricked into feeling like we are stuck in bad situations forever when we are in a situation that genuinely has no solution. We often feel as though we just have to accept the pain and continue to suffer in the situation. This is learned helplessness.

However, there is a real advantage to working on resolving problems, because in the future it may become resolvable. Even small steps to build strength, cultivate resilience, and find resources to help tackle the situation you feel stuck in can help free you of feelings of helplessness and hopelessness.

Case example in abusive relationships:

A place where learned helplessness can manifest is in chronically abusive relationships. The partner who is being abused can begin to feel like nothing will change no matter how much they try to change their partner or improve the relationship dynamic. Eventually the abuse victim can feel so helpless that they stay in the relationship for the foreseeable future. Abuse victims can suffer in silence for years.

A major takeaway from feeling constantly helpless is that there is almost always something you can do to improve the situation you are in, even if the things you do can’t fully resolve the situation. You can take steps to improve the situation over time, and with each positive step forward, you can learn to overcome feelings of helplessness.

Learned Helplessness: Experiment with Dogs in a Cage

There was a series of famous psychological experiments done by psychologist Martin Seligman in 1967 at the University of Pennsylvania involving dogs and learned helplessness. 200 dogs were shocked randomly in a cage, causing them to be taught that they couldn’t escape. When shocks occur without a pattern, it is the fastest way to convince experiment subjects (animals or humans) that they can’t escape.

When the dogs were shocked randomly, 192 of the 200 stayed in the cage. Experimenters called the eight dogs “psychotically optimistic” because they wouldn’t stop trying to get out of a cage. Only eight out of the 200 show how powerful learned helplessness can become.

How does this relate to humans? PET scans have shown that the prefrontal cortex doesn’t work as effectively in people with depression versus people who are not experiencing depression.

The prefrontal cortex relates to making rational decisions, thinking through tough problems, and coming up with solutions to problems. So if we are stuck in the dog cage of our problems, and it feels like no matter what we do we fail to change our situation, our prefrontal cortex can shut down and we experience learned helplessness.

Systemic Oppression and Helplessness

One example of learned helplessness can be the numerous systems of oppression in society. My take on learned helplessness is not to argue that every problem is solvable by the oppressed without holding the oppressor accountable. However, there are things we can do to feel more hopeful, even with century-long oppressive systems pushing us down.

To approach feeling helpless within systemic oppression, start by being realistic about what the problem is. Accept what the problem is. This process could be difficult and limiting. It’s not about ignoring problems, such as saying racism doesn’t exist. Systemic oppression is absolutely real.

Here is an example of pushing through learned helplessness in a chronically ill client:

Chronically ill clients are sometimes told by others statements such as “push through”, “don’t worry”, “it’s going to get better”, and/or “keep trying.” Sometimes these statements are really counterproductive advice. We don’t want to ignore the reality of a situation. We don’t want to ignore people’s pain.

If you’re in a cage and the whole cage is being shocked, teaching someone to run around all the time might exhaust them and make them feel worse. In this case, think if it is the whole cage where you’re being shocked, or just the one square? Then we can make a change and decide where to put our energy.

Tap your foot in other spaces in the cage to see if it’s any better. This process is not about ignoring systemic issues, but acknowledging them. A question to ask yourself is within this oppressive structure, how can we still be as healthy as possible? We can give ourselves permission to be human or hurting, without having to feel extra shame or guilt.